WHY CAN’T WE JUST LOCK UP THE BAD GUYS?

Understanding What the

Heck is Going On

You can also get this and all Underground Classroom, Mad Sociologist, and Video projects with at Substack.

Curriculum Specifications

- Course: Social Studies–US Government

- Education Level: Advanced Middle School and High School

- Reading Level: 6.96

- Read Time: 16 minutes

Lately, we’ve been hearing a lot of debate on this thing called Due Process. We read in the news or see on our social media feeds how “illegal” immigrants are being rounded up and deported, even sent to foreign prisons. On one hand, the state is making the claim that these people are criminals and gang members and pose a threat to the country. On the other hand, you may have read some responses decrying the fact that they were denied this weird thing called “Due Process.”

Yeah, what’s that all about?

Well, I’m about to explain.

To understand Due Process, and why it is important, we first must understand the concept of “rights.”

Do you have rights?

Of course!

Prove it. Show them to me. How do you know you have rights?

Uh…I just have them

Okay, so let’s break this down. You have rights because you just have rights…that’s not much to go on. But that’s the way of it. Rights are tenuous things. They don’t exist in any real sense.

Because rights are a story that we tell about ourselves and about the country we live in. It’s a story in which we, as human beings, have rights. We have the right to free speech. We have the right to worship. We have the right to do business. In other words, it is taken for granted that we can do these things and nobody, specifically the government,1 is allowed to stop us.

In the United States the story about our rights is familiar. It can be summarized in one sentence that we have all been exposed to…

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men2 are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator3 with certain unalienable rights, that among these are life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.

Sound familiar? This is the story that we tell ourselves about our rights.

First, we all have them.

Secondly, we all have them in equal measure.

Thirdly, they are unalienable. In other words, they cannot be taken away from us

Finally, these rights can be defined in terms of life, liberty, and pursuit of happiness.

Well, wait a minute! What do you mean they can’t be taken away. We send people to jail all the time. Isn’t that taking away their right to liberty?

Yes. Good observation.

You see, there’s one more thing about rights that is not explicit in the story we tell but is implicit in the very assumptions about what it means to have rights.

Namely, exercising my rights cannot impose on you exercising your rights. This is the balancing act. I can’t say, “according to my religion, you need to do my homework for me.” No. I may have a right to my religion, but that right in no way imposes upon you. If I am able to force you to do my homework for me, in other words, to impose my rights upon you, that’s not a “right.” That’s a privilege.

Through most of human history, people lived in societies that prioritized privilege. In other words, those in society who had more power were able to impose their will on those with less power. In democratic societies, however, we prioritize rights over privilege. And, for the most part, we prefer it that way.

However, power discrepancies still exist. And that’s not necessarily a bad thing. Some power discrepancies exist for a reason. For instance, your teacher has the power to assign you homework…and has the power to impose a grade on you based on your conformity to that power.

But in exercising that power, there are constraints to what the teacher can assign with regard to homework. For instance, your teacher cannot assign you an essay in which you must deny the existence of God. Doing so may be a violation of your right to worship freely. Or, conversely, your teacher cannot require you to make a profession of faith if you choose not to worship.

In other words, rights are a constraint against the unreasonable exercise of power. Some exercise of power is necessary. Your society has decided that it is appropriate to mandate that young people go to school or undergo some kind of formal education. In school, your principal and teachers can exercise the power to require you to take certain classes…even the boring ones. They can constrain your behavior to the extent necessary for the school to function for everyone. Society has decided that this is a reasonable imposition on the freedom of young people. You may not like it, but there it is.

However, your teachers and principal do not have unlimited power. There are things they cannot require you to do because you have certain unalienable rights.

Well, that makes sense. What does that have to do with putting people in jail?

The problem is that sometimes people will use their power or exercise privilege in ways that impose against other people’s rights. For instance, I cannot go into your home and take your stuff. That’s a violation of your right to property. But what’s to stop me? Let’s say I’m bigger than you, or I’m armed, and there’s no way for you to physically stop me from coming into your house and taking your stuff.

I would call the police

Exactly. The state has created institutions, and empowered individuals to protect your rights. These individuals have a very special and very serious position. They are empowered to even use violence if necessary to protect your rights. If someone breaks into your house, you don’t have to just let them do what they want…and most importantly, you don’t have to take matters into your own hands and put your well-being or even your life on the line. You can call the police, and the police will take it from there.

In this case, the state is empowered to send the police who have the power to stop this person from violating your rights. The state also has the power to punish those who violate your rights by denying them their right to liberty. The state has the power to take away a person’s rights if they abuse their liberty to impose on other free individuals.

Of course! That makes total sense!

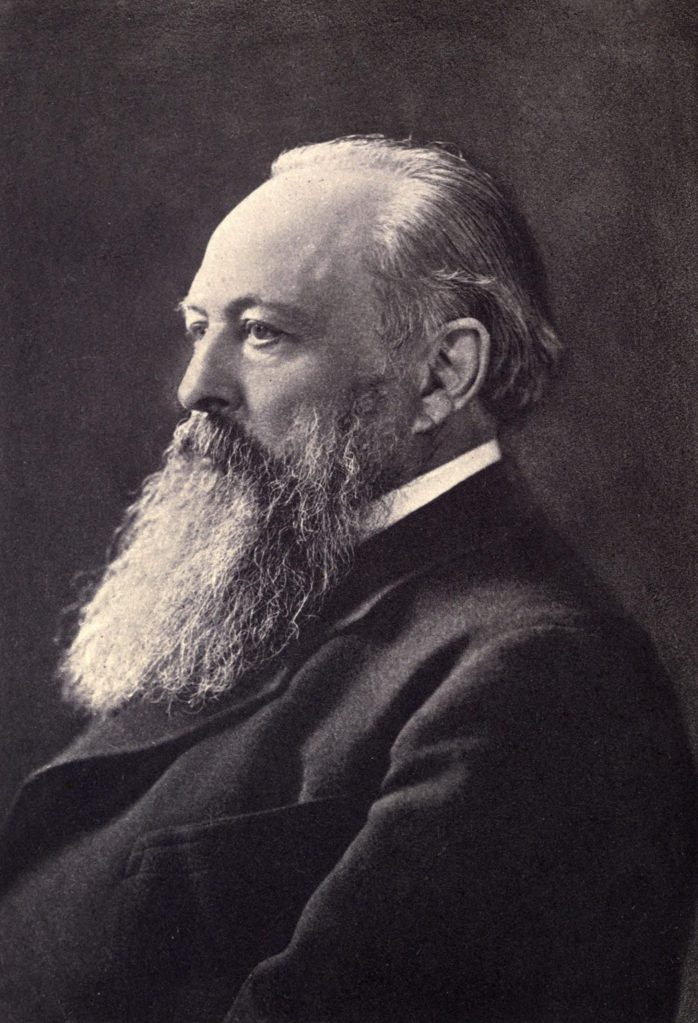

Ah…but here’s the thing. When society says that the state has the “power” to do something, to impose on people’s rights to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, that’s a dangerous proposition. There’s a guy named Lord John Emerich Edward Dalberg-Acton, otherwise known as Lord Action, who famously said, “power tends to corrupt, and absolute power corrupts absolutely.” You always have to remember this. Power corrupts. When the state is empowered to do a thing, it will likely try to abuse that power.

Let me put it to you like this.

Hey! You stole my wallet! You owe me $1000 dollars!

No I didn’t

Yeah? Prove it!

Um…I don’t have your wallet.

That’s just like a thief, hiding the evidence!

You get where I’m going here? I can accuse you of violating my rights. I can abuse my power. And then you are stuck…except, society has rules about this–rules designed to mitigate those, especially the state, who might abuse their power.

You see, it’s not good enough for me to accuse you of stealing my wallet. I must prove that you stole it. You are not required to prove that you did not steal it. We do this because there is no way to prove something did not happen. There are ways to prove that something did happen. There’s evidence.

Consequently, before the state can deny a person their rights to life, liberty, or the pursuit of happiness, it must satisfy something called Due Process. In other words, the state must follow certain procedures to justify imposing its power against an individual’s rights.

Due process can be broken down into two kinds. Procedural Due Process, and Substantive Due Process. Let’s start with the Procedural kind.

Here’s the scenario. Your house was broken into and some valuable items were stolen. You call the police. This is the first step in due process. The police begin the process by taking your story, collecting evidence, and conducting an investigation. They may know of three people in the area with a history of breaking into houses and stealing stuff, but they can’t just go and lock all three people up. They can go and ask them questions.

But here’s the thing. When they go and ask those suspects questions, the suspects do not have to answer. You see, individuals have a right to not incriminate themselves. This is part of that Substantive Due Process. The police must follow a procedure in conducting an investigation to figure out who stole your stuff. But the suspects have a Substantive Due Process to exercise their rights against self-incrimination, even if it makes it more difficult for the police to do their jobs and get your stuff back. In other words, the suspect has a right to remain silent according to the Supreme Court Case, Miranda v. Arizona. The right to remain silent is not explicitly stated in the Constitution, but it is implicit in the right to privacy and the right to not incriminate oneself. Because of Substantive Due Process, the police cannot force a suspect to confess.

And for good reason. We know that if enough force is applied, people will confess to stuff they didn’t do. It’s a way of protecting everyone’s rights.

Well, the police conduct their investigation, protecting everyone’s rights. They are informed by a witness that one of the suspects has items in his garage that match the description of your stolen items. The police cannot just go and bust down the guy’s door, rush into the garage, and take back your stuff. They are constrained. They must continue following Procedural Due Process. They must go to a judge and get a warrant. A warrant is issued when a judge feels there is enough evidence to temporarily suspend someone’s right to be secure in their property to effectuate a search. The police must prove that they have a compelling reason for exercising the warrant.

They get the warrant, enter the house, and sure enough, they find your stuff. They also take the suspect’s fingerprints which turn out to match those found on your window and in your home. They have the stolen stuff. They have the fingerprints. They have the witness. They have a confirmed history of breaking into houses. In other words, they have evidence. The police then make the decision to arrest the suspect.

Yeah! That’s compelling.

But it does not end there. The police’s actions are only temporary. They have enough evidence to bring the suspect in for questioning, against his right to be free to go about his own business, and even to hold him in jail for a time. However, the suspect has a right to an attorney…someone knowledgeable in the nuances of Due Process…and the right to a trial by a jury of his peers.4

Procedurally, the defense attorney will advise on the best course of action for the suspect’s case and work to get the best outcome for their client. The suspect has the right to be heard in court, to contest any evidence against him, and to advance his own story. Maybe a friend of his asked him to store these items without telling him the items were stolen.

Regardless, a suspect in a criminal case is assumed to be innocent until proven guilty. He does not have to prove that he is innocent. The state must prove that he is guilty. In other words, the state carry’s the burden of proof.

This is really inconvenient, but it is the most important value in our criminal justice system. This is what keeps the government from just arresting anyone they want and locking them away. The state must be able to prove that it has a compelling interest in denying someone their rights to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. Being guilty of a crime is a compelling interest.

The suspect, however, is not guilty of the crime legally and procedurally until the jury comes back with a verdict of guilty.

Wow! Okay. So what about immigrants and non-citizens?

That’s the debate. Here’s the deal. In order for this Due Process to protect the rights of individuals, the same process must apply to everyone. According to the 5th Amendment of the United States Constitution, “No person shall be…deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law;” For many of us, that seems pretty clear. If you are a person, and you are under the jurisdiction of the United States5 then you have a right to Due Process.

Others contend that Due Process rights should only apply to citizens. Therefore, immigrants, especially immigrants who have entered or remained in the United States illegally, should not be protected by Due Process Rights.

Others contend that there are so many illegal immigrants that allowing all of them to exercise their rights to due process is too much of an impediment to dealing with the fact that they are in the United States illegally. Therefore, the state has a compelling interest in denying such immigrants their due process rights.

It’s tricky because without due process, the state has the power to grab just about anyone, accuse them of being an illegal immigrant, and ship them out of the country. Recently, the United States has been shipping accused “illegals” to a questionable prison in El Salvador. This is a problem because the state is taking on a great deal of power in making the claim that it should be able to deport and imprison people without Due Process.

And what is the consequence of power according to Lord Acton?

Reports indicate that many of those deported to the El Salvador prison, called CECOT had not been convicted of a crime. Many were not even undocumented. One of the most controversial is the case of Kilmar Abrego Garcia, whom the administration admits it sent to CECOT by accident, yet despite a court order, have as of the time of this essay yet to free.

The state accuses Garcia of being a gang member. Which may or may not be true.6 However, remember what was just discussed. In the United States, a suspect is not guilty until a jury declares him so. Kilmar Abrego Garcia has never been convicted of being a gang member. Nor was he in the country illegally.

What if he is a gang member, but the state does not have enough proof? Or what if he is a gang member and it takes so long to convict him?

That is a problem. The American legal system isn’t perfect. In the United States, our legal system is designed to protect the innocent from being denied rights without justification. The focus is on ensuring that the convicted really is guilty. The idea is that it is better that a hundred guilty people go free if it protects one innocent person from being imprisoned accidentally.

That means there are a lot of points of contention. Trials have a lot of rules that protect the person being tried. Even at that, the person being tried could be found guilty of a crime and appeal that conviction, theoretically all the way to the Supreme Court. This takes a lot of time an energy.

And resources. Someone has to pay for all of this. In the United States, we have a big problem with people who do not have the resources to defend against accusations in court. Many find themselves in jail without being convicted of a crime, but unable to make bail7. In essence, they are in jail because they are poor. In the meantime, wealthy people can hire very skillful lawyers who excel at navigating due process, giving them a huge advantage over the less fortunate.

We also have a problem with systemic racism8. We know that black people and people of color in the criminal justice system are disproportionately represented, disproportionately found guilty, disproportionately imprisoned, will disproportionately be disciplined in prison, will disproportionately serve longer sentences. The disproportionality of race-based discrimination at every level of the criminal justice system is a problem that we have yet to resolve. Some prefer to silence the debate than deal with the problem.

There are plenty of examples of people slipping through the cracks of the criminal justice system. Some have been convicted despite being not guilty. Some avoid conviction despite being guilty as heck.

That doesn’t seem fair.

The alternative is to approach criminal justice from the idea that taking away the rights of a single person is an acceptable price to pay if it means taking a hundred criminals off the street.

I can see that.

What if it’s you who is expected to pay that price?

Well…uh…that would suck!

Yes it would.

The bottom line is that Due Process is the system we have in place to protect individual rights from being denied by a powerful state. To date, the dominant argument has been that all persons have these unalienable rights, and therefore, Due Process should apply to everyone.

We are currently engaged in a debate about this, with a significant political block making the claim that Due Process is, in effect, a privilege accorded to citizens. Furthermore, there are times when guaranteeing due process is too burdensome in the state’s efforts to protect the security of its citizens.

The counter-argument is, if the state can decide who benefits from Due Process, it is taking upon itself the power to determine who does and does not have rights. Is that a power you think the state should have?

Where do you stand on this very important issue.

Footnotes

- Henceforth I will use the phrase, “the state” in referencing government. This term is more specific and refers to the actual organization responsible for doing the work of government. ↩︎

- All human beings ↩︎

- Or by virtue of being human ↩︎

- Jury of his peers is a confusing term in the United States. In the United States, it just means a jury of citizens. Historically, some societies had systems called Peerage, in which some people had noble standing, others had common standing. A jury of one’s peers simply meant that in such societies, common people could not be judged by a jury of noblemen, or noblemen could not be judged by a jury of common people. The United States does not have such a system. ↩︎

- Under the jurisdiction, for the most part, means that you are in the United States or on land belonging to the United States. You are, therefore, subject to United States’ law. An exception may include a diplomat who is given immunity from American law. There are separate processes in such a case. ↩︎

- In my opinion and the opinion of many experts in this field, it is almost certainly not true. ↩︎

- I’ll get into bail maybe in another post. I don’t want to go down this rabbit hole. Bail is money that a suspect must put up to be released from jail. The idea is that putting up this money will dissuade the suspect from fleeing and not being held accountable. The counter argument is that someone who cannot afford bail ends up remaining in jail despite not having been convicted of a crime. ↩︎

- Your teacher may not be allowed to talk about this. Systemic racism means that the legal system itself creates obstacles and disadvantages to people based on race. ↩︎