I Keep Hearing Different Things

That is a good question. Reality is often lost in political rhetoric and bantering. Sometimes we find ourselves supporting policies because they are the policies of my team, a cognitive bias. To think like an economist, however, means we should evaluate policies based on their associated costs and benefits. Let’s take a look at tariffs.

The first thing you need to know is that economists rarely speak in terms of “good” or “bad.” When economists look at policies like raising or lowering tariffs, what they are looking at is the cost as compared to the benefits and how they may align with policy goals. It’s not a matter of, “is this economic tool good?” It’s a matter of, “will this economic tool accomplish what you are setting out to accomplish at a reasonable cost?”

This is why among the first things we learn in Economics class is the concept of Opportunity-Cost. Opportunity-Cost is the value of what you are giving up as compared to the value of what you will gain. You have $100. You can spend that money taking Betty-Sue out for pizza, or you can spend that money on game night with your buds. Or you can put that money in your bank account. If you choose to take Betty-Sue out for pizza, the opportunity cost is you don’t have the money for game night, if that were your next best option.

What this means is that you perceived that pizza with Betty-Sue was more valuable than having those hundred dollars in your account or using it for game night. Way to go, Betty-Sue!

Well, of course I’m taking Betty-Sue out for pizza!

Of course! But in doing so you are still giving something up. There is no “good” decision or “bad” decision economically speaking. We are just looking at what you value. And this value may have nothing to do with money. There is no way to objectively measure the dollar value of your time with Betty-Sue. All we know is that this pizza date is worth more to you than $100.

Cool! So, how ’bout answering my question

The decision to apply tariffs works exactly the same way as the decision to take Betty-Sue out for pizza. You have to ask, what are you trying to accomplish, what are the costs, and what are the benefits?

Tariffs are taxes placed on imports.

I hate taxes! I don’t have to pay those, do I?

Well…it’s complicated. Here’s how it works.

I own a widget company and I want to sell my widgets in your country. It costs me $20 to make the widgets. I’ve done the market research and know that I can sell my widgets in your country for $30. I can make a 50% profit. Good deal. I start shipping my widgets to your country.

Whoa, now wait a minute! You say. We have our own widget manufacturers in this country, but it costs domestic manufacturers $30 to make widgets. That means domestic manufacturers have to sell widgets for more than $30 if they want to make a profit. If you come in with your cheaper widgets, you will outcompete our domestic widgets and force them out of business, or force them to offshore their manufacturing, costing our country jobs! Can’t have that.

To protect your country’s widget manufacturing sector, you apply a 50% tariff on all widgets entering the country. As the importer, I’m paying the tariff directly. But this tariff is, from my point of view, an added cost associated with selling my widgets in your country. I am going to add the cost of the tariff, or at least a significant portion of the cost, to the price of my widgets. It now costs me $30 to sell widgets in your country, so I have to charge consumers more to compensate.

I am paying the tariff, or the import tax, directly. But as a cost of production, I’m going to pass on the value of the tax to the consumers by raising my prices. If you are a widget consumer, then the opportunity cost is that you are paying more for the widget than you otherwise would have paid if there were no tariff. In essence, you are paying the tariff indirectly.1

Well, that sucks! I don’t want to pay taxes either directly or indirectly!

From your point of view as the consumer, you are right. You will pay more for your widget.

On the other hand, if you owned a widget company, or maybe you work for a widget company. This changes your point of view. You don’t want to lose your business or lose your job because a foreign company can produce cheaper widgets. Tariffs force more competitive producers to raise their prices. This protects less competitive domestic industries and jobs from being lost. This is why tariffs are referred to as Protectionist policies. They protect domestic production by increasing prices.

That’s the opportunity cost associated with tariffs. The benefit is in protecting domestic markets or potentially encouraging foreign companies to build their manufacturing in the domestic market, thus retaining and even creating jobs. The cost is that consumers will pay more for the products than they otherwise would. The question is, is this trade off worth it? Again, there’s no right or wrong answer. It depends on your role in the market. If you are an investor or a producer, you might support the tariff. If you are a consumer, you might not.

Let’s look at a real-life example of how this works.

Right now, the best Electric Vehicles (EVs) in the world, according to most observers, are made by the Chinese company BYD. The BYD Han is a high-quality EV that retails at a lower price than American EVs. BYD is one of the best-selling car companies in the world, with almost 600,000 more units sold than Ford, it’s nearest American competitor.

Wow! I’ve never heard of BYD.

In 2018, President Trump placed a 25% tariff on Chinese EVs. In 2024, President Biden increased those tariffs to 100%! For BYD to sell it’s EVs in the United States, it must double its sticker price! The goal is to protect American EV manufacturing, which is lagging behind the Chinese industry. It worked. You don’t see many BYD vehicles in the United States, but you do see an increasing number of American EVs on the roads.

However, the cost is that American consumers are paying more than they otherwise would if we applied free trade2 policies to Chinese EVs. They are also, arguably, getting a lower quality vehicle.

If your priority is to protect U.S. manufacturing of EVs, tariffs are great! If your priority is to get the best quality EV at the lowest price, tariffs are not so great. Again, there’s no good or bad about it. It just depends on your priorities.

Well, I’ve heard that tariffs will bring prices down eventually.

No.

That is a misunderstanding of what tariffs are for. Tariffs are for protecting domestic industries. They do this by increasing prices. There is no mechanism by which tariffs will reduce prices.

Yeah, but tariffs increase revenues for the government…so maybe we’ll pay lower taxes. That will save us money, right?

Afraid not. If the government cuts income taxes as a result of increased revenue from tariffs,3 that’s merely shifting the tax burden from income tax to tariffs. Remember, as the consumer you are paying all or almost all the cost of the tariff through increased retail prices on goods. The money you might save from income tax you are losing to increased consumer costs. It’s a wash.

Furthermore, income from tariffs account for only 1.5% of federal revenue. Tariffs would have to be increased far beyond current levels to be a meaningful source of income for the nation, let alone replace income taxes. Economists agree that the market would not respond well to such a vast increase in consumer prices. We’ve already seen how angry people get about inflation.

I heard there was a time when tariffs covered almost all of our federal spending. What happened to those good ol’ days?

Again, good and bad are relative terms. We can go back to 1830’s standards of federal spending if our nation chooses to. The cost would be no more Medicare. No more Social Security. No more Medicaid. No social safety nets. Reduction of the military to about 5000 troops. No more research, education, agricultural or any such funding. Most Americans do not think the costs outweigh the benefits.

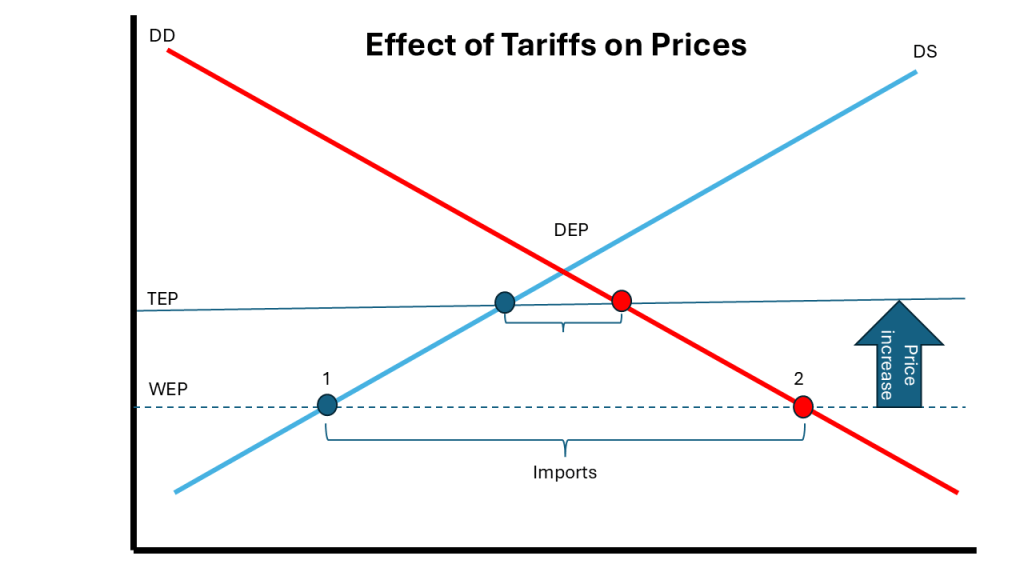

So, there you are. This was a quick primer on tariffs that can be summarized in the Supply and Demand Chart above. DEP represents the Domestic Equilibrium Price. This is the equilibrium price of the product without foreign competition. However, once a foreign company can produce the product more cheaply, that becomes the World Equilibrium Price (WEP). At the World Equilibrium Price, domestic manufacturers will only be willing to produce so much of the product, Point 1 on the Domestic Supply curve (DS).4 The Domestic Demand (Point 2 on the DD curve), however, is much higher, more than domestic suppliers are willing to supply at that price. Demand must then be met by increasing imports. Meanwhile, domestic suppliers will reduce their production to meet the World Equilibrium Price.

Tariffs are designed to avoid this problem by creating a Tariff Equilibrium Price. The tariff raises prices closer to the Domestic Equilibrium Price (DEP). This increases domestic production and decreases the demand for imports. The higher the tariff, the higher the domestic prices, the lower the demand for imports.

Now let’s complicate things even further…

Or, we can just leave it alone…right?

Nope. Let’s complicate things!

For instance, it’s one thing to put a tariff on, say, cars. Putting tariffs on cars will cause the prices of cars to increase, which may be a good tool for protecting car manufacturers. Cars are a finished product, therefore it is easy to calculate the total impact of tariffs on the price of cars.

What happens when we put tariffs on production goods? Production goods are the materials purchased by manufacturers to produce their finished goods. Let’s say we put a tariff on steel. Now we have a more complicated situation because there are a lot of things made from steel. This would cause the price of everything containing steel to increase. Yes, this could mean that more steel production would take place in the United States, but that does not reduce the prices. If increased production happens, it’s because the prices are higher.

Or we can take a product like coffee. There’s a huge demand for coffee in the United States, however, Hawaii is the only place in the country suitable for growing coffee. Hawaiian coffee growers cannot possibly meet the demand for coffee all over the country. Therefore, regardless of the tariff, there is little to no savings to be found in domestic production. Consumers are stuck with the higher prices even if Hawaiian coffee producers can compete with foreign production.

How about a blanket tariff on all goods coming into the country. Well, now that would be really complicated because in modern markets, supply chains often cross borders multiple times. Again, car manufacturing is a great example. For any given car, parts are imported and exported across the U.S. border multiple times. A parts manufacturer may import a production good from Canada to make a part that will be exported to Mexico, to be used in the manufacture of an engine that will then be imported back into the United States, attached to a chassis that will be exported to Canada to finish the body work, then re-imported back into the United States…etc. Each crossing of the border will add to the cost of production, applying multiple tariffs in the production of a final good.

Finally, other countries make their own decisions, and just like your decision to take Betty-Sue out for pizza, economics isn’t always the priority. Putting a tariff on, say, Canadian steel might encourage Canada to retaliate by placing tariffs on Wisconsin cheese. A Wisconsin cheese producer may not purchase steel from Canada, but because of the steel tariff, his costs for exporting his product just increased, reducing demand. He may have to cut production if he is not able to find other markets for his cheese.

So, there it is. Tariffs as a policy are not good or bad. There are legitimate reasons to use tariffs. But just like any other economic decision, there are associated costs. There may also be unintended consequences if a full understanding of the relevant supply chains are not clearly understood. It’s important for you to know what tariffs are and how they work if you are to evaluate policy makers who either support or oppose tariffs.

The question is, how is this policy going to impact me, or my community? How does this impact my economic goals?

If you are a Substack fan, you can see all of my work, including The Mad Sociologist posts, video commentary, and soon, fiction and poetry, including pre-publication access. Click Here

Footnotes

- Of course, it may be more complicated than that. As the importer, I may be willing to sacrifice some profit and take on some of the value of the tariff myself. So, you the consumer may not be paying the full value of the import tax. But you are going to pay at least some of it. Regardless, prices for widgets are going to be higher than they otherwise would be if not for the tariff. ↩︎

- Free trade means no, or very low tariffs between nations ↩︎

- This is a big “if” considering the size of our federal deficit and national debt. ↩︎

- I know. I know. It’s a straight line. I don’t make up the rules! ↩︎