Current Events Explainer

On Inflation and Why Prices Go Up

The so-called “expert” economists keep saying that inflation is going down, but I can see prices continuing to go up. Are they stupid?

This is a question I hear all the time when talking to people and see on social media. It’s certainly a question that economics teachers are likely to get, especially if they teach higher level courses or have higher level students in their classes. I figured I would take a moment to go over the answer and break it down in simple terms.

What is Inflation?

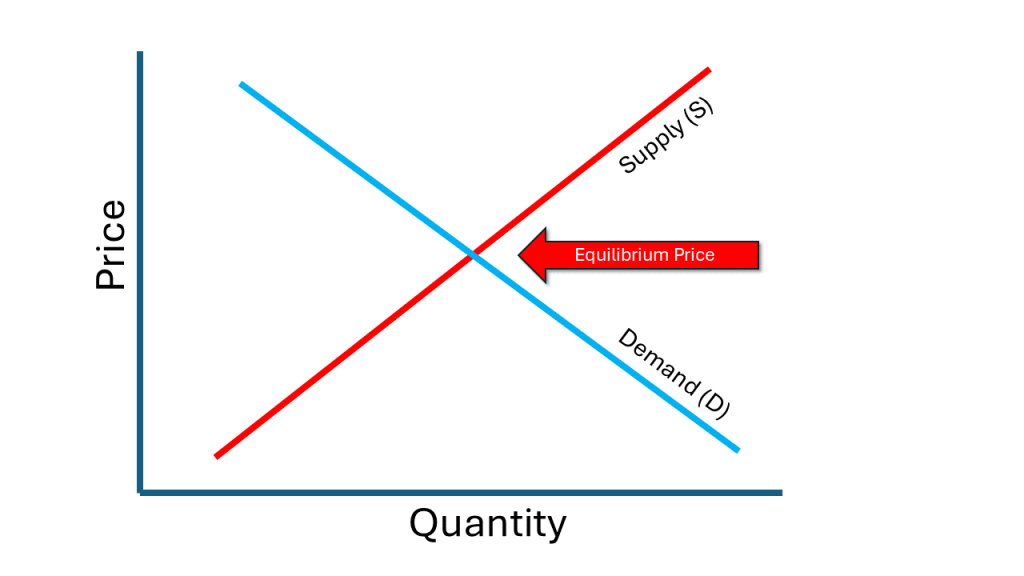

First, we want to understand what inflation is. In brief, inflation happens when there is too much demand pursuing too little supply in a market. What does that mean. Well, let’s start with a simple Supply and Demand Curve or graph.

A supply and demand curve shows the relationship between the price of a good or service and the quantity desired at a given price. The blue line is the Demand Curve, represented by a downwardly slopping line (Inversely proportional, or negative slope for the math geeks). We know this is a Demand Curve because we all demand/want stuff, but the more expensive it becomes, the less we want it (Law of Demand), hence it slopes downward, representing the quantity desired increasing as the price decreases. The red line is the Supply Curve. It’s the opposite because it comes from the point of view of the person supplying the good or service. In that case, the higher the price for a given good or service, the more likely I am to want to supply it (Law of Supply). Hence, the line is sloping up (Directly proportional, or positive slope). Obviously, as the demander, I optimally want the good or service for free! As a supplier, I want to sell the good or service for a bagillion dollars! Since neither of those things are going to happen, we have to compromise. Where the demand curve meets the supply curve, that’s the Equilibrium Price. In other words, this is the price by which I as the supplier will sell all of my goods and services that I’m willing to sell at that price, and everyone who wants that good or service at that price will get it. If, for instance, I’m selling hamburgers, at the equilibrium price everyone who wants burgers at that price will be satisfied, and I will have no hamburgers left over. Everybody is happy1.

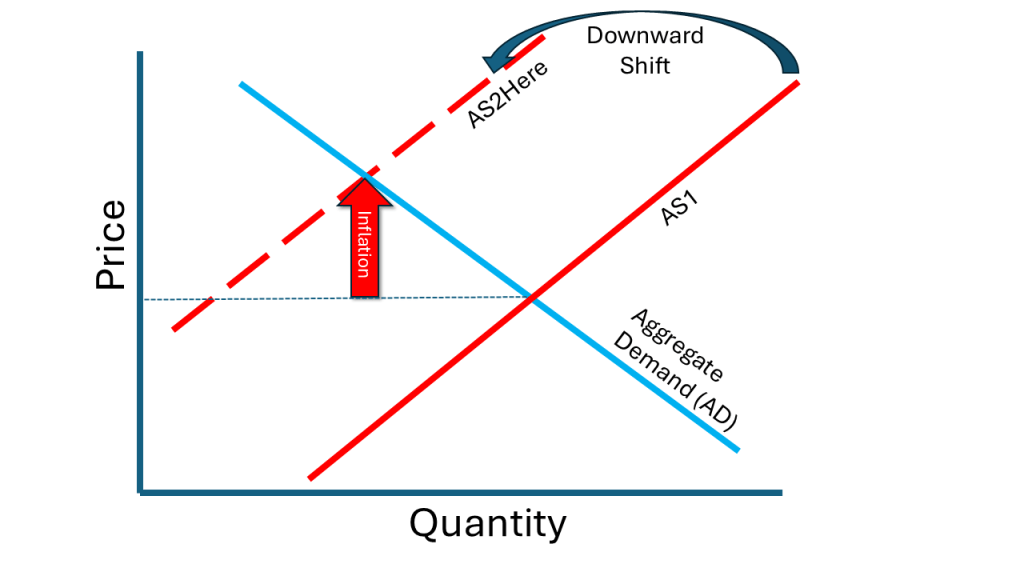

This works for a single commodity like hamburgers, but we can also use the same curve to model all of the prices of all of the goods and services offered in a market. We can take the aggregate of all of the goods and services and model2 how they would look on a supply and demand curve. In this case we are looking at Aggregate Supply, or the total goods and services producers will be willing to offer in a market, and the Aggregate Demand, the total goods and services desired in a market, and create a supply and demand curve for everything.

Guess what. It looks exactly the same! Just different labels!

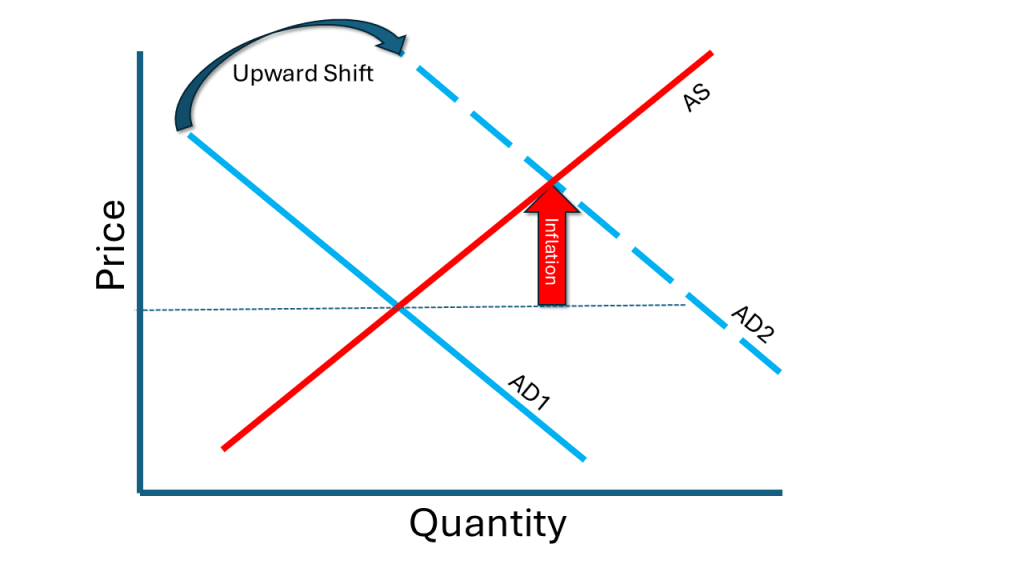

Inflation happens under two conditions:3

- A downward shift in the supply curve

- An upward shift in the demand curve

Here we can see an example of a reduction in supply represented by a downward (leftward) Shift in the Aggregate Supply Curve from AS1 to AS2.4

Here is an example of Inflation resulting from an increase, or rightward shift in Demand.

Cool! So, um…How ’bout answering the question

Yeah yeah! Hold on! I’m getting to it. Sheesh!

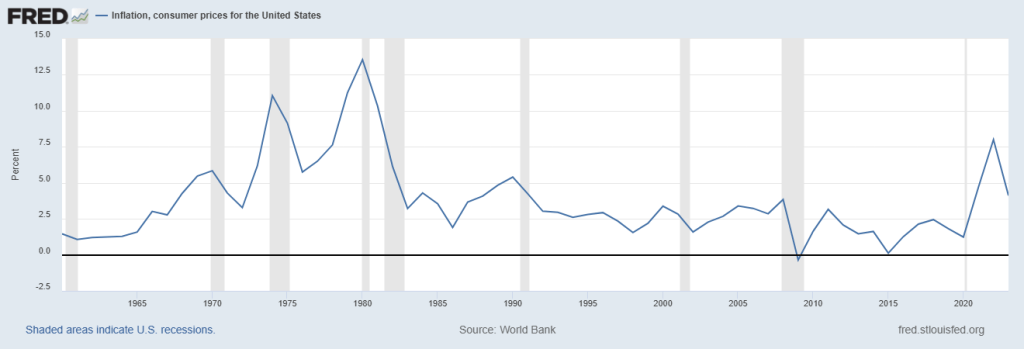

Under normal circumstances inflation is manageable. Here’s a breakdown of U.S. Inflation since 1960 that I got from the Federal Reserve Economic Database (FRED)5

You’ll notice there were some really nasty peaks of inflation in the 1970’s. This was the inflation that most students grandparents still complain about. It was pretty bad.6 Then there was the peak that we see in 2022. That was the period of inflation that we just recently went through. This is the stuff your parents were complaining about.7 For most other years, inflation hovered somewhere around two percent.

What does this mean?

Well, when economists track inflation, what they are doing is tracking the price of goods and services as compared to a given time in the past. This graph is looking at annual change, so it is taking the price of goods and services and comparing it to the price of those goods and services this time last year. That’s the source of the confusion. Economically speaking, inflation has come down. It was as high as 8% in 2022.8 In other words, goods and services were, on average, eight percent more expensive in 2022 than they were in 2021. Which was bad because, on average, goods and services were four and a half percent more expensive in 2021 than in 2020.9

Currently, inflation is down to about 2.9%, pretty close to the standard level. That means that goods and services today (number is from July, but…you know…) are, on average, almost three percent more expensive than they were in July of last year. Prices are still going up. Inflation is down, but it is not zero.

Why not? Why can’t Biden get inflation down to zero?

Okay. So, there’s a lot going on in that question.

First, let’s get one thing out of the way. The President of the United States, regardless of party, has very little to do with inflation.10 Regulating inflation is mostly the responsibility of central banks. Central banks are responsible for regulating the amount of money in a given market. In the United States, the central bank is the Federal Reserve. The Federal Reserve (The Fed) does a lot, but the most important things they do is loan money to member banks, and fund government debt by purchasing Treasury Bonds. It is through these actions that the Federal Reserve responds to economic trends.

There are some things a president can do, but when it comes to inflation, those things are often very unpopular. They also have a limited impact.

The Federal Reserve, on the other hand, can make borrowing money more or less expensive. This is the key. Here’s a dirtly little secret of a national economy. Debt is how the economy grows. We don’t like to talk about it. Our parents always tell us to avoid going into debt. Save our money. Put it in the bank. Minimize how much we borrow. That may be okay advice when you are a young person just starting out. It’s aweful advice for running an economy.

If you want the economy to grow, you need more money in the market. To increase the amount of money in the market, people have to borrow. Think about it. Let’s say that we had a market that consisted of a hundred people. Each person had a thousand dollars to spend. If we let this market do its thing for a year then came back and looked at it, we might see that twenty individuals now have two thousand dollars. That means the other eighty percent is left dividing up sixty-thousand dollars, or about $750 each. The economy hasn’t grown. The money has just shifted hands. That’s a zero sum game. One person’s gain is another person’s loss.

To grow an economy you need to break the zero sum game. Money needs to be added to the economy. You need a means of creating money and getting to people who will invest it.

In the U.S. that’s the Fed. And the process of adding money to the market to grow the economy happens through debt.

Let’s say you have a great business idea. To get it off the ground, you need $100,000. You have good reason to believe that after five years you will be able to make $200,000 on this idea. But you don’t have $100,000 in your pocket. You have to borrow. You borrow $100,000 at five percent annual interest. After five years this will cost you $127,628.16. You made over $70,000, divided by five that’s $14,000 a year. That may be worth it. You invest, and in doing so you benefit, but the economy also grows because of the $70,000 in value that you added to it.

But at ten percent interest, it will cost you $161,051.00. That’s only less than $8,000 a year. Now it may not be worth it. The interest is too high for you to invest in your business idea. If you don’t invest, the economy does not grow.

That’s how the Federal Reserve works. During times of economic recession, when the economy is shrinking, it lowers the cost of borrowing. At two percent interest, your investment will only cost you a little over ten thousand dollars. You make $90,000, or $18,000 a year. You might be able to quit your day job. You have an incentive to borrow.

Wait! Where does the Federal Reserve get this money?

That’s the beauty of it. It prints it. The Federal Reserve is a government controlled monopoly on the production of dollars. That’s cool! The Federal Reserve can print as much as it wants, but it still has this problem with regulating the economy. Too much money, means increased demand, means inflation. Not enough money means decreased demand and recession. They have to get the amount of money in the market, called the Monetary Base, just right, what I call the Goldilocks Level.

During an economic recession, the goal is to get more money into the market to incentivise spending and investing. The Fed makes it easier to borrow by making its loans to member banks cheaper. It also purchases treasury bonds at lower interests rates, making it easier for the government to borrow.

During times or inflation, however, the opposite is true. In this case, the economy is growing too fast. There’s too much money in the market, and suppliers cannot keep up with the demand that this money creates, so they raise prices. The Fed’s goal then is to decrease the amount of money in the Monetary Base. It does this by disincentivising borrowing. It raises the interest by which it loans to member banks and increases the amount of interest it will accept on government bonds. When money is harder to get, peope spend less and invest less.

The thing is, we always want the economy to grow. We never want it to shrink. This is obvious during a recession. But this is also the default during normal economic times. The only difference is in how fast we want the economy to grow. During a recession, we want the economy to grow quickly to alleviate suffering. In normal times we want it to grow more slowly to avoid too much inflation. But to do this we have to accept a certain amount of inflation.

The bottom line is that there are certain prices for things that we want to go up. There are price increases that we like. Take, for example, housing. When you buy a house for, say, $200,000 you’re doing so with the understanding that the value of that house will go up over time. In ten years you may want to sell your house. When that happens, you want to sell it for $300,000. That’s inflation. If you own a home, you like it. If you don’t own a home, you are unlikely to invest $200,000 if there’s no prospects for inflation. You’re better off renting.

Well, if housing inflation is going to happen, then people are going to demand higher wages and salaries so they can afford to pay their rent, or the mortgage payment on a house. Wage and salary inflation is a price paid by suppliers that non-suppliers like. It incentivises us to work. If wages and salaries don’t increase over time, our incentive to work goes down.

When we invest in the stock market, we are expecting the value of our stocks to increase. That’s inflation. Shareholders want the values of the companies that they are invested in to increase. That’s inflation. They want more profits this year than last year. That’s inflation.

The hope is, of course, that what we gain from the inflation we like is compensated by deflation, or prices going down elsewhere in the market. Televisions, for instance. Once upon a time, to buy a smart television with all the perks was very expensive. But businesses have an incentive to make televisions more efficiently over time and reduce the costs of production. That tends to bring the cost of televisions down. Now, smart TVs are relatively affordable. Also, there are plenty of used TVs that people can get their hands on for almost nothing.

To recap, growing the economy means people must be willing to take on debt. Debt adds money to the market, making money easier to get, incentivising spending. People only borrow if what they get on the back end is greater than the value of the debt they take on. At zero percent inflation the economy is a zero sum game like that described in the small economy described above. The investor only gains from someone else’s loss. Since people don’t want to lose, they are less likely to purchase what I’ve invested in. So, I’m not likely to invest in anything.

Moderate inflation allows us to create an economy that is not a zero sum gain. I will invest in a good or service because I know I will gain value on the back end. You will purchase my good or service because you gain something that you value more than the money that you are spending.

The problem is when inflation gets too high. Then you as the spender are less willing to spend because the value of what I get from the good or service no longer compensates me for what I’ve spent.

Get it? A certain amount of inflation is necessary to help the economy grow, but too much inflation disincentivises spending. We need a Goldilocks level of inflation that incentivises borrowing, but does not disincentivise spending and investing. Central bankers refer to this as Target Inflation. Economists have settled on 2% as that Goldilocks Target Inflation.

Why 2%?

Um…well…

…It turns out that there really is no objective, empirical, scientifically tested reason for two percent. It just kinda feels right. Two percent inflation doesn’t piss people off.

It also gives the central bank enough wiggle room to respond to economic crises that may lead to recession. The interest rates it charges to keep inflation at two percent are low enough to incentivise borrowing, but high enough that the bank can lower them when facing a possible recession.

There is, however, a debate going on about what the Target Inflation should be. Some economists are arguing that the Fed should accepted a Target closer to three percent for fear that holding their interest rates high for too long could create a recession. Investors, on the other hand, would prefer a lower target because that increases the real value of their investments.11

Why We Should Hope Prices Will Not Go Down

The bottom line is , in normal times, we can expect the prices of the goods and services that we purchase to be, on average, two percent higher than they were a year ago. If our wages increase by more than two percent a year (which is wage inflation) then we really don’t mind so much. So long as enough people in the market are enjoying wage/salary increases greater than the inflation rate, or can expect that they will enjoy better wage/salary increases in the future, then people don’t get too upset with inflation.

However, we have just gone through a period of high inflation where people saw increases in their wages/salaries eaten away or even lost by inflation. That makes people angry. We want relief. We want prices to fall. When they don’t fall, we get upset, at least until our wages/salaries catch up and we feel we are making progress again.

Remember, in normal times, prices will go up. Also, we want that to happen. Let me give you an example.

Take another look at the Inflation Graph.

There’s only one time on that graph where you see prices actually falling, represented by negative inflation. That’s 2009, when inflation was -.36%. That was a time when prices actually fell. Did that make people happy?

Absolutely not!

The context of those falling pricess is what we today call The Great Recession. Millions of people, including myself, lost their jobs. Millions lost their homes. Trillions of dollars in wealth evaporated. Furthermore, the entire nation lost faith in their economic and political institutions causing ramifications that we are still experiencing today.

Was all of that suffering worth that one third of one percent decrease in overall prices?

Of course not.

As it stands right now, the Federal Reserve’s goal at the onset of our most recent inflation crisis was to raise interest rates in small increments. Their goal was to bring inflation back down to the Target Inflation Rate of two percent without causing a recession. The goal was not to reduce prices. This should have been communicated better.

Many economists were skeptical that this could even be done. If you look at the graph above, the shaded areas are recessions. Sharp decreases in inflation are correlated to recessions. Economist Larry Summers predicted that we would need to raise unemployment to ten percent in order to get where we are right now with inflation. That’s millions of people out of work. Fortunately, it looks like the Fed’s strategy is working. Inflation is almost down to the target. We did not experience the recession levels of unemployment and disinvestment predicted–at least so far.

It’s frustrating because we expect prices to go back to what they were before the inflation spike. That’s not going to happen. It was never going to happen. And though it’s frustrating and problematic now, in the long run, it’s a good thing. The level of suffering necessary to bring prices down is not worth the costs.

Notes

- Okay, not everybody. There will still be people who cannot afford the hamburgers at the Equilibrium Price, and still those who think the Equilibrium Price is too high. They may not be happy, but they won’t show up to buy my burgers anyway, so toheckwittum. ↩︎

- Remember, these are models. We don’t have to use real numbers to get the concepts. That’s what a model is for. The model is used to make theoretical predictions about how a market might act. Now, economists can use real numbers and make calculations. They’re pretty good at it, but the numbers rarely ever turn out exactly as predicted. ↩︎

- Really three. We can see inflation happen as a result of monopoly power, but that’s outside of what I want to talk about here. ↩︎

- I don’t want this explainer to be too long, so I can get into why these shifts might occur in a later explainer ↩︎

- When studying economics, FRED is friend ↩︎

- Again, explainer for another day. ↩︎

- Another thing you will notice is that the peak in 2022 isn’t nearly as high as the peaks in the 70’s. Be careful when the Floating Heads in the Magic Box in your living room talk about “unprecedented inflation” or “inflation like we’ve never seen before.” They are being hyperbolic because that sells advertising space. Inflation was bad, but not unprecedented. ↩︎

- It was as high as 9%. This graph is looking at annual inflation. If you break it down by month the peak reaches 9%. For my purposes this is not important ↩︎

- It’s important to note that inflation was unusually low in 2020 because of the COVID Recession. ↩︎

- An explainer for another day ↩︎

- Think about it. Let’s say I invest a thousand dollars in a five year investment that will get me fifteen hundred dollars. That’s great. But the higher the inflation, the lower the benefits when it comes time to spend that fifteen hundred dollars. If it costs me fifteen hundred dollars to purchase the same amount of goods that it cost me a thousand dollars to purchase five years ago, I’ve not made any money in real dollar value. ↩︎

Reason prices are high and keep going higher is because of Trump’s corporate tax cuts by 14% while American individual taxes increased each year, Trump’s tariffs causing shipping containers to increase in price by 70% – 80%, and Trump spending increasing deficit to its highest in history all causing inflation to take off during Trump term and continue into Biden term dramatically driving up the price of goods. Trump made it so corporate tax decrease and tariffs could not be removed and are set to expire in his term and price hikes will only get worse under trump with his 29% decrease in corporate tax and higher tariffs on imports. Trump wants to privatize healthcare using UHC of which healthcare premiums and prices will soar for consumers because UHC has to keep their shareholders happy and rich. Cost if homes, cars, food, and other good will continue to rise under Trump because of his corporate tax cuts, tariffs snd spending driving up deficit further which will increase inflation further. We are headed for Reaganomics under Trump. Get out if the stock market and put your money in safe money where it earn an inflated interest rate. Warren Buffett and Jamie Dimon have sold more than half their shares of stock this year in 2024 and are sitting on a pile of cash and font care if the cash burns jokes in their pockets. Writer of this article must be a Republican, not an economist. Do agree deflation can lower prices at cuts of jobs. But we are headed for recession if s as other depression.

LikeLike

Sorry it took me so long to approve your comment. It got lost in the shuffle somehow. Anyway, part of my thesis in this post is that presidents have relatively little control over inflation. Yes, blanket tariffs will certainly cause inflation, but that’s an exception that proves the rule. A president has to do something pretty extreme to influence inflation as much as we saw in Biden’s early term. That being said, we should apply the same standards to evaluating all presidents. The policies that you describe above may all be true…and they may even be bad policies, but did they cause the inflation that we saw in 2021-2023? Hrmmm…unlikely. The best estimates I could get on this was that the total deficit spending from the pandemic, and that would have included Trump’s and Biden’s deficit spending, explain maybe at best about 10% of the total inflation in the U.S. It certainly explains none of the inflation that other countries experienced. One thing we can say is that government relief, whether through deficit spending or not, certainly contributed to the savings that people stored up during the pandemic. As restrictions were lifted, people wanted to spend that savings at a rate that suppliers could not keep up with. That, according to most economists, explains most of the story. Thank you so much for responding. My goal is to have a dialogue.

LikeLike